Yesterday, 29 year-old Karl Anderson pleaded guilty to a racially-aggravated common assault on Manchester City and England footballer Raheem Sterling, and was jailed at Manchester City Magistrates’ Court for 16 weeks. He was also ordered to pay £100 compensation and a mandatory Victim Surcharge of £115.

The reported facts are that, shortly before Manchester City’s match with Tottenham Hotspur last Saturday, Anderson approached Mr Sterling outside City’s training ground, kicked him four times to the legs and called him a “black scouse cunt” and “nigger”. A nasty assault, albeit one which fortunately did not cause any serious injury. And some commentators have questioned whether 16 weeks’ custody is a sufficiently robust sentence for a racially-motivated assault by a man with a history of football-related violence.

So let’s break it down. We should start with some essentials.

What is “racially aggravated common assault”?

Common assault is the least serious form of assault on the criminal violence hierarchy, involving the infliction of minimal injury. (Technically, a “common assault” does not in fact require the use of any physical force at all; merely causing in another the apprehension of immediate unlawful force, say by squaring up to someone. “Assault by beating” involves the application of unlawful force – i.e. physical touching – but in practice the terms “common assault” and “assault by beating” are often (incorrectly) used interchangeably. It has little practical significance, as the two offences are created by the same statutory provision – section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 – and carry the same maximum sentence. But it’s a neat example of how no-one, including those of us who practise it, really understands the complexity and caprice of the criminal law.)

Anyway, common assault (or assault by beating) is a summary offence, meaning it can by itself only be tried in a magistrates’ court, and carries a maximum sentence of 6 months’ imprisonment. The racially aggravated version of this offence (which was created by section 29 of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998) is “triable-either-way”, meaning it can be tried either in a magistrates’ court or a Crown Court, and carries a maximum sentence of 2 years’ imprisonment. An offence is racially aggravated when one of two criteria is satisfied:

- At the time of committing the offence, or immediately before or after doing so, the offender demonstrates towards the victim of the offence hostility based on the victim’s membership (or presumed membership) of a racial group; or

- The offence is motivated (wholly or partly) by hostility towards members of a racial group based on their membership of that group.

So far, no problems in seeing how the offence was made out.

How should a court approach sentence for this offence?

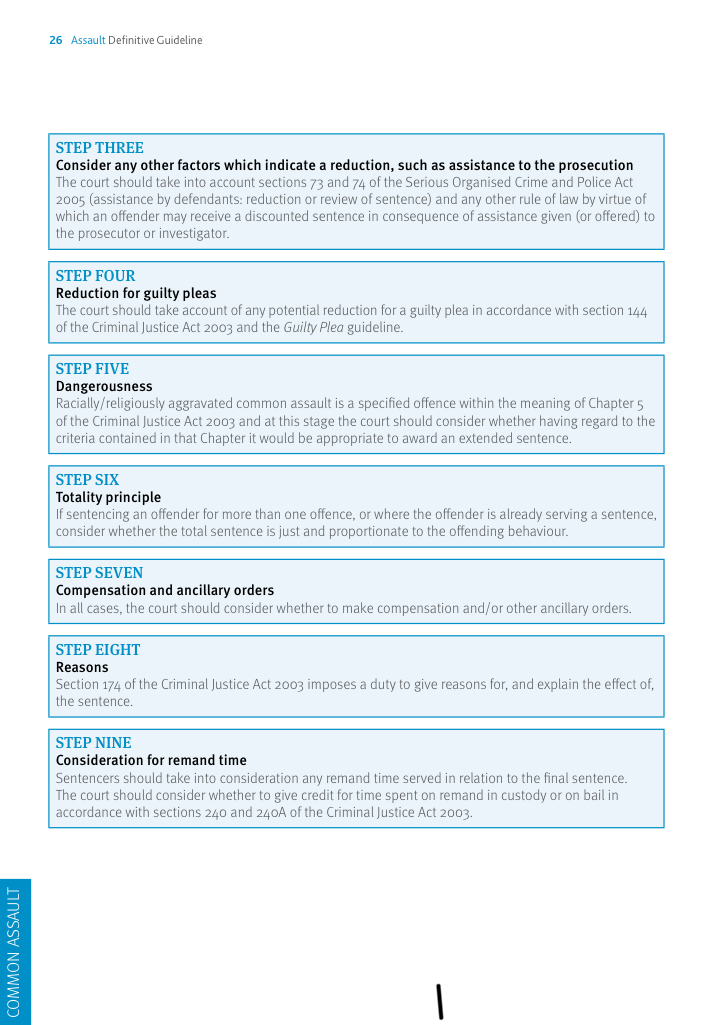

The magistrates’ court was required to follow the relevant Sentencing Guidelines published by the Sentencing Council, in this case the Assault Definitive Guideline. Courts will also consider any relevant decisions by the Court of Appeal in similar cases.

The approach prescribed by the Guidelines (and by the Court of Appeal) is that courts should determine the appropriate sentence without the racial element, and then determine the appropriate “uplift” to reflect the racial aggravation. The level of the uplift will depend on the aggravating features which include the level of planning; the offence being part of a pattern of racist offending; membership of a group promoting racist activity; deliberately setting up the victim for humiliating him; the location of the offence; vulnerability of the victim; whether victim was providing a service to the public; whether timing or location of the offence maximised the distress caused; and whether the expressions of racial hostility were repeated or prolonged (R v Saunders [2000] 2 Cr App R (S) 71; R v Kelly and Donnelly [2001] EWCA Crim 170)

So let’s work this through. As ever, we have limited facts available to us, because the magistrates, notwithstanding that they were dealing with a case involving a high profile international footballer which was bound to attract national attention, did not see fit to publish their sentencing remarks online through the official judiciary.gov website. One wonders exactly how many storms there have to be over misreported sentencing decisions before the judiciary gets the message, but that’s a soapbox for another day.

But doing what we can with what we have, the Guardian reports:

“Magistrates were told Anderson pulled his white van alongside Sterling’s car as the forward waited to enter the training ground. CCTV showed both men get out of their vehicles and Anderson walking towards Sterling.

Miles said Anderson, who had been in the vehicle with his partner, started shouting racial abuse at Sterling and called him “you black scouse cunt”. He said Anderson also told the footballer: “I hope your mother and child wake up dead in the morning, you nigger.”

Miles added: “He approaches Mr Sterling and can be seen to be bouncing on the balls of his feet. He sets out kicking Mr Sterling to the legs on four occasions.” The court was told Sterling’s left hamstring was sore after the attack but he did not sustain serious injury. Miles said: “He is a professional footballer. His legs are important for his job.””

The Manchester Evening News adds that Sterling suffered bruising to his legs.

The Guideline requires that the court identify a category of offence by reference to the presence of features of harm and culpability. The category then provides a starting point, and a range through which the court can move as it considers the aggravating and mitigating features. You can have a go yourself:

The assault, to my eye, falls clearly within Category 1, before we even consider the racial element. This involved repeated blows and the presence of bruising renders this a serious injury in the context of a common assault/assault by beating, so greater harm would appear to be established. Higher culpability is present by use of kicking (a shod foot is counted as a weapon equivalent in offences of violence). And the other aggravating features – this was an unprovoked attack on a man at his place of work, targeting the tools of his trade, his legs – would push this upwards in the range.

And then we come to Anderson’s previous convictions. The Guardian reports that Anderson had 25 previous convictions for 37 offences, including throwing a flare at a police officer during a football match. The MEN gives further colour:

Among his offences, Anderson was jailed for 18 months in July 2016 for violent disorder; convicted of common assault in April 2016; failed to comply with an international football banning order in January 2016 and November 2015; and a racially aggravated public order offence July 2014.

He was among a group of eleven Manchester United fans who were handed three and five year bans in January this year.

There is little reported by way of mitigation. There was, it seems from the Manchester Evening News’ live-feed of the hearing, no Pre-Sentence Report before the court. The expectation is that a court will seek a report, prepared by the Probation Service, if it is considering imposing custody, unless a report is considered not necessary. Its absence suggests that there were no matters of particular mitigation – such as mental or physical health – that would have been relevant to sentence. The defendant expressed remorse through his solicitor, and his early guilty plea is by far the strongest point in his favour.

Against this backdrop, I would have expected a standard assault by beating to be sentenced towards the top of the sentencing range, close to 6 months’ imprisonment (before reduction for guilty plea). Reducing by one third to reflect the guilty plea (all guilty pleas entered at the first hearing are rewarded with 1/3 off the sentence) would give us just over 17 weeks, which is close to the 16 weeks received.

But we haven’t yet moved to the uplift for racial aggravation, which can be substantial, and, as the Guidelines state, can move the sentence beyond the range for an ordinary common assault. Although the court is required to explicitly state publicly what uplift is being applied to reflect racial aggravation, there is no report of the magistrates having done so in this case. Quantifying the uplift is difficult; the Court of Appeal once suggested that up to 2 years would be a reasonable uplift for racially aggravated offences, but given that 2 years is the maximum sentence for this offence, some proportion is required. Cases are always fact-specific, so drawing assistance from earlier cases is always tricky. Nevertheless, to offer a little context:

- In R v Fitzgerald [2003] EWCA Crim 2875, the Court of Appeal imposed 10 months’ imprisonment for racially aggravated harassment, alarm or distress with intent (which carries the same statutory maximum as racially aggravated common assault). The Defendant had shouted racist abuse at people in the street, and had unleashed a torrent of racial abuse and threats towards a police officer as he was arrested and taken to custody.

- In R v Rayon [2010] EWCA Crim 78, the Court of Appeal imposed 10 months’ imprisonment (including a 5 month uplift) for racially aggravated common assault where the Defendant punched the victim to the face, threw him to the floor and kicked him. He used racist abuse, although the judge found that racism was not the primary motivation for the attack (it was against the background of an ongoing court case).

- In R v Bell [2001] Cr App R (S) 81, the Court of Appeal imposed 12 months’ imprisonment, including a 6 month uplift, for racially aggravated common assault where the defendant attacked a 65 year-old black man in the street, calling him a “black fucker”, knocking him to the floor and telling him he should be “in a concentration camp and shot”.

- In R v Higgins [2009] EWCA 788, the Court of Appeal approved 18 months’ detention, including a 12 month uplift, for racially aggravated common assault where the defendant was part of a group that pursued the victim through a park, making racist comments and threats, and punched him in the face and attempted to choke him.

An important point is that all of these were decided before the introduction of the Assault Sentencing Guidelines, and so are further limited in their utility. Nevertheless, allowing that sentencing is an art, not a science, and that no doubt other lawyers would reach a different conclusion, my view is that, in Anderson’s case, a starting point of 5 months with an uplift of 4 months would not have been unreasonable in the circumstances. That would result in a sentence of 9 months, reduced to 6 months (or 26 weeks) to reflect his guilty plea.

Where does that leave us?

It means that, in the context of racially aggravated offences, Anderson was in my view sentenced leniently, although the sentence is perhaps not as surprising as it first appears when one considers the example sentences above. What might certainly be said, however, is that the sentences for this type of pernicious, low-level racialised violence are probably lower than most lay people would expect. And, momentarily mounting my high horse, the man on the street would be entitled to demand exactly what a 16-week sentence (of which the defendant will serve a maximum of 8 weeks) is intended to achieve in the case of this repeat racist offender. Precisely zilch rehabilitation will be achieved during that period. It punishes to a degree, although Anderson has served significantly longer periods in custody, and may feel able to do 8 weeks with relative ease. It can hardly be said to be a deterrent sentence. And, adding those together, it’s difficult to see how the public are any safer for this sentence. None of the statutory purposes of sentencing appear to be satisfied.

It is, in many ways, what I would call a typical “magistrates’ sentence”: A short period of custody likely to achieve diddly squat, at enormous public expense. I don’t put the blame solely on the shoulders of the sentencing court; they operate in a culture where this type of sentence for this type of offence is considered appropriate. But, frankly, if we have racist hooligans repeatedly inflicting racially-aggravated violence on members of the public, my preference would be that we either aggressively rehabilitate them under a lengthy and intensive community order, or, if we have exhausted all options and punishment has to be king, lock them up for a period of time that appears commensurate with the seriousness of the offence.

It is of course possible that my criticism is misguided, and that there were beautifully set-out sentencing remarks, including a full explanation for the length of sentence and an exposition of the uplift, which render my take unfair. If so, I would welcome corrections and a copy of the sentencing remarks.

Of course the other option open to magistrates in a case like this is to remit the sentencing to Crown Court with a maximum tariff of 2 years imprisonment. While I agree that the sentence appears lenient, we only know the bare facts and know little or nothing of the representation from either CPS or his solicitor.

I’ve been a magistrate for twenty years and would never sentence a crime of this type without a pre-sentence report.

It is more the forensic analysis of sentencing policy that is good. He/she has in the past analysed some of the ‘lenient’ sentences that go on the front page of the Daily Mail and shown that they are exactly in line with the guidelines. My view is there should only be the broadest of guidelines (if any at all). I think that was the Major’s view.

Sent from my iPhone

>

Sentencing guidelines you quote are for the Crown Court.

Could they have committed him for sentence?

Aren’t the mags maximum powers 6 months, and if he pleaded at the first opportunity 1/3 off?

Tied hands?

Very informative article. Minor point, but I don’t think it’s quite accurate to say that common assault is “created” by s. 39 CJA 1988. “[C]ommon assault by beating remains a common law offence”: Haystead v CC Derbyshire [2000] Cr App R 339, 340.

As a magistrate who has seen cases I have judged reported in the media, I know how easy is it to get the facts wildly askew. I t’s impossible to make definitive comments about a case unless you have been in court to hear all the evidence, watched the demeanour of the defendant, looked carefully at the previous and listened to what the defence lawyer has to say.

The one quibble I have with your thorough and thoughtful analysis is that the injuries may not have been seen as serious in the context of the offence. The victim in this case did not apparently require medical attention or take time off work. To some extent this is a consequence of CPS chronic under-charging of offences against the person. Earlier this year I sat on a charge of assault where the victim was beaten black and blue by a large lump of wood, and serious bruising, lacerations and unconsciousness and concussion are far from rare.

On what we can know of this case, the sentence would seem to be lenient and it might have been sent up to Crown Court because magistrates’ sentencing powers are insufficient. In my view, the trail of similarly nasty convictions would probably have swung me in that direction. However, it’s marginal. It could have been that the early guilty plea could have been recognised by not sending it up. This would be in line with recent initiatives to encourage us to keep trials of marginal cases out of Crown Court, and to use our initiative in sentencing.

SB raises two issues relating to magistrates’ courts and sentencing:

1. We do tend to dish out short jail sentences.

But I am far from alone in doing it without any real expectation that it will do any good. Often there simply is no alternative. A fine would be an insult to the victim; the defendant is unsuitable for unpaid work for one of many reasons; the drink and drug rehab people won’t or can’t take them (denial, lack of cash, recent failures); curfew is out because of unsuitable or no accommodation; probation simply hasn’t got anything useful to offer int he rehabilitation line.

Imprisonment is still fairly rare, but I wish it were infinitely more so. Society is unwilling to tackle the real root cause of crime – poor or insecure accommodation, effective social security, sensible drugs policy, adequate mental health services, etc. Doctors used to bleed patients because they could think of nothing else to do, and maybe we are using prison in the same way.

2. Sentencing Remarks

On my bench at least we are not encouraged to make Sentencing Remarks like we hear judges make when we sit on appeals in Crown Court. For one thing, we tend not to feel as removed from clientele as judges do, and I for one would worry about slipping into sententious cliche when addressing people from whom I might only be removed by a couple of pieces of bad luck or a genetic tendency to addiction. (I cringe for judges and sentenced sometimes.)

What we do instead is Reasons. This, essentially, is what bits of the trial swayed us one way or another, or which aspect of the total information before us has pushed us into a particular sentence. These are usually short and to the point, which is good. And they usually go straight into the file and are never seen again, which isn’t. If I am on a sentencing bench I always have to ask specifically to see the trial bench’s Reasons. Which is bonkers, because without them your decision is based on the 2-minute case summary given by the Crown, and the pre-sentence report which all too often is just the defendant’s self-justifying account which, as we say, lacks credibility.

I don’t know how we would go about putting out Reasons up online, and (stupidly) have never thought about it till now. Something to raise with the Bench committee at some point.

And now to dinner.

Another excellent piece!

Two queries:

1 .As they are surely recorded by the Court, would it not be appropriate for ALL sentencing decisions to be posted on-line after sentence?

2: The sentence appears to be based on the effect of the assault, why not on the intent?

1, Sentences are recorded, but reasons and comment are (in my area) written more or less legibly on the cheapest copier paper, sometimes signed and dated, and then tucked into the case file. In practice, seem to be there mostly to cover the backs of our legal advisors.

2. Who knows. It goes back to what I said about needing to be in court and paying attention before being able to make complete sense of verdict or sentence. Intent can be very, very hard to judge with any certainty – especially how much alarm or damage the defendant intended. Words or actions that would pass unnoticed in the middle of a Sunday game on Hackney Marshes would be more serious in the lobby outside our courtrooms, for example.

Given what we do know about the case, I agree it looks lenient to me and ought to have been committed to the Crown Court for sentence. There are plenty of seemingly lenient sentences at Crown Court too so I don’t think the magistrates concerned should be too severely criticised.

I see the usual dig from about magistrates, in this case about imposing short sentences and, for a change, I suspect you may be right in this this time. The implication seems to be that District Judges sentence differently – is that right then? I do wonder how much work you actually do in Magistrates courts – you do seem oddly bitter towards them.

Regarding the point made by a poster about pre-sentence reports: usually that would be the case, but for a defendant with an extensive record like his, and perhaps even a recent report, immediate custody isn’t unreasonable in these circumstances. I’d say immediate custody is rare in magistrates cases in my experience but the statistics are probably available. On the face of it, this seemed like a good candidate for a long spell in custody.

‘ …….But, frankly, if we have racist hooligans repeatedly inflicting racially-aggravated violence on members of the public, my preference would be that we either aggressively rehabilitate them under a lengthy and intensive community order, or, if we have exhausted all options and punishment has to be king, lock them up for a period of time that appears commensurate with the seriousness of the offence…….’

Like

I give not a hoot whether it was “racially aggravated” – stupid bloody law. I do care that an entirely innocent party has assaulted by a chap with a substantial record of criminal violence. Lock the sod away for a few years.

Minor point: is it a crime to accuse the entirely innocent Mr Sterling of being “scouse”? If not, should it be?